“You can design and create, and build the most wonderful place in the world. But it takes people to make the dream a reality” Walt Disney

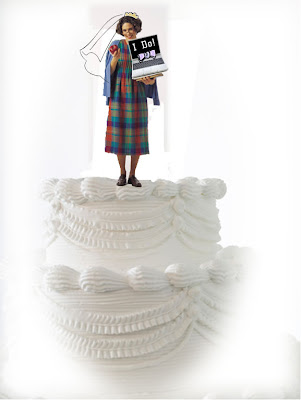

This seems like pretty basic “Teaching 101”, but achieving this isn’t as easy as it sounds. Creating lessons that are indeed magical, is in itself a feat worthy of Disney-style fireworks. If we want our students to really be engaged in what they are learning, they need to be involved in the designing and creating process. Researchers, theorists and educational experts refer to this as “Constructionism”, but I’m going to call it

This seems like pretty basic “Teaching 101”, but achieving this isn’t as easy as it sounds. Creating lessons that are indeed magical, is in itself a feat worthy of Disney-style fireworks. If we want our students to really be engaged in what they are learning, they need to be involved in the designing and creating process. Researchers, theorists and educational experts refer to this as “Constructionism”, but I’m going to call it a) Walt Disney

b) Mickey Mouse Teaching sounds way more fun than "Constructionism”

b) Mickey Mouse Teaching sounds way more fun than "Constructionism”

So let me tell share one example of what I think good quality Mickey Mouse teaching looks like. There are about a bazillion (my all-time favourite teacher questions this term) different ways to incorporate Mickey Mouse teaching into a classroom. This is just one way and I would love to hear about others, so please be sure to leave me a comment!

Generating and Testing Hypotheses:

In a nutshell, we’re talking about posing a question, postulating the answer, and investigating the actual outcome, right? So let’s bring in Mickey and see if we can’t generate some magic!

Nasa’s Design a Planet has to be one of the coolest, most magical interactive tools I have come across in the last year. This interactive web site allows the user to create a new planet based on what is already known about existing planets. The tool challenges users to create a planet that can sustain human life. By manipulating numerous variables, the user is guided through a process of creating this new world.

This interactive, animated tool requires users to consider the impact each variable has on the resulting planet. Will there be volcanoes? Tectonic plate movement? Water - what form? What will the planet's orbit and mass be? What kind of sun will the planet have? My first planet was not able to sustain life, and the tool explained why.

This interactive, animated tool requires users to consider the impact each variable has on the resulting planet. Will there be volcanoes? Tectonic plate movement? Water - what form? What will the planet's orbit and mass be? What kind of sun will the planet have? My first planet was not able to sustain life, and the tool explained why.

TELL me that isn’t cool!

This is such a great Mickey Mouse Alberta

- Grade 9 (Space Exploration) examines technologies available to us for space exploration

- Grade 6 Science examines control of variables, and Topic C Sky Science focuses on planets, and Earth’s relationship with its surrounding celestial bodies.

This process of posing questions, predicting answers, and examining outcomes doesn’t have to be limited to scientific or mathematical settings. We can use this model for any inquiry based learning we want to present.

Check out this video from Apple’s Challenge Based Learning web site to see how this model can be applied to investigating the social significance of voting.

This same process works for any subject area for virtually any grade level. But remember, Mickey Mouse-ifying

There are scads and scads of fantastic project based learning web sites. Here are a few that might pique your interest!

- http://pbl-online.org/ is a good resource for getting you started with project-based learning in your classroom.

- Not sure WHERE to start? Consider the best practices discussed at http://www.saskschools.ca/~bestpractice/project/index.html from Regina Public Schools.

- If you need a few ideas to get your Mousey goodness flowing, check out some Project Based Learning examples from the US Department of Education at http://www2.ed.gov/pubs/SER/Technology/ch8.html

So roll up your sleeves and BE the Mouse!